The Global Forest Watch reported more than 97,500 square miles of the earth’s tree cover vanished last year, an area eleven times the size of Belize (1). Wildfires affected 6.2 million people between 1998-2017, attributing 2,400 deaths, and substantial irrecoverable ecological and economic losses worldwide, the Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED) reported. The United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction warns that, due to Climate Change, the size and frequency of wildfires will grow and its impacts on Latin America and the Caribbean will be tremendous (2).

Belize’s Wildfires

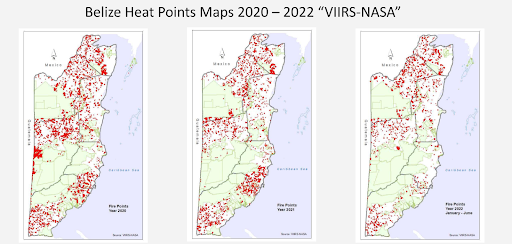

In Belize, changing climate regimes means longer wildfire seasons, and hotter droughts. Despite this concerning outlook, many human activities contribute to the increased size, severity, and frequency of wildfires. Records in Belize show that wildfires destroy more than 97,260 acres of forests annually and they contribute to significant biodiversity loss, deforestation and forest degradation (3). Between 2019 and 2022, more than 5,090 fire alerts were recorded and in the northern, central and southern regions these conditions have been extensive (1).

“The rainy season does not eliminate the risks and impacts of wildfires,” warns Mario Muschamp, Terrestrial Manager at the Toledo Institute for Development and the Environment. “While the rainy season alleviates some discomforts caused by wildfires, the lingering dangers remain.” As one of Belize’s Fire Experts who has been working for more than 20 years in the field of forest fire ecology and forest fire management, Muschamp speaks candidly on the historic and recent wildfire behaviors and trends. Muschamp informs that long after wildfires have been extinguished, the risks of erosion, flooding, reduced water quality, and other ecological and economic losses increase. He adds: “Too often, many people assume that the dangers are gone after wildfires, but the reality is that our problems have only just begun.”

The Impacts

Of the multiple forest threats, fires may have some of the more profound and lasting impacts on people living nearby.

“The first and foremost threat is to life and property,” says Muschamp. As a fire-fighter, he has seen the dangers that wildfires can do to life and property.

When fire ravages a forested area, it also has direct social and economic bearing on forest-dependent peoples and rural communities. Muschamp recounts that in 2020, many farmers in the southern region lost homes, and a sizable percentage of their crops and cocoa farms because of escaped fires. “It devastated livelihoods, and local timber, agriculture and tourism industries,” Muschamp recalls. He added: “These landscapes and resources are essential for indigenous peoples and local communities either for their supplement or as a direct source of income.”

“No threat has more profound and lasting impacts on forests and people than the one posed by wildfires.”

Belize’s forests and landscapes are important for goods and services that serve as an economic safety-net for thousands of forest-dependent peoples, but wildfires are a direct and real threat to their livelihoods and ways of life in both the dry and rainy seasons.

While there is still uncertainty about the extent of damage on an annual basis, wildfires also continue to undermine sustainable forest management efforts. For instance, the timber sector continues to be impeded by large annual economic losses due to uncontrolled wildfires (3). However, the destruction is more than just merchantable trees.

Apart from socio-economic impacts, wildfires have destructive ecological consequences and remain the greatest threat to the long-term survival of Belize’s forest and agricultural landscapes. According to the World Health Organization, hotter and drier conditions are drying out ecosystems, increasing the risks of wildfires. As wildfires increase both in frequency and severity, recurrent wildfires reduce the recovery rate of forest species (4). Fires eventually alter the forest structure, composition and cover in several critical areas. Indeed, fires have been known to impact on soil and watersheds, causing soil erosion, removal of forest vegetation near waterways, and eventually impacting water quantity and quality (4).

Wildfires also trigger health impacts. Air pollution caused by wildfires is known to release massive quantities of carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide and fine particulate matter into the atmosphere (2). The resulting health effects include respiratory and cardiovascular problems, as well as mental and psychosocial impacts (2).

POTENTIAL CAUSES

Muschamp explains that while there are some specific natural factors contributing to wildfires, most wildfires in Belize are caused by escaped agricultural fires and arson. Belize Forest Department officials agree and acknowledge that although “slash and burn” is a widely accepted practice for land clearing and food security, many farmers rarely apply the proper controlled fire techniques and most often ignore fire regulations (5). The second major cause of wildfires is arson by illegal hunting fire practices, illegal burning of waste, and poor camping practices (6).

Muschamp explains that while escaped agricultural fires are common, many farmers employ poor fire practices because of a lack of monitoring and enforcement. He asserts that the enforcement of wildfire laws and regulations is weak. “The thing about Belize is that we have fantastic laws but weak enforcement,” he says. He asserts that this is not the result of unwillingness by officers to enforce the laws and regulations. “On the contrary,” says Muschamp, “ many of us, both at the national and local levels, want to enforce the fire regulations, but political interference often impedes enforcement.” Yet, enforcement is necessary and critical to ensure that agricultural fires are managed appropriately, and that conditions that make uncontrolled wildfires detrimental are prevented and addressed.

Changes Needed

National Level: Muschamp knows that there is more that the government can do to manage wildfires. He emphasizes that it is also time to implement “The Wildland Forest Fire Management Policy and Strategy” developed in 2009. “We have yet to implement it,” he says. Several attempts to implement the policy and strategy were unsuccessful, and Belize is still waiting to integrate a coherent forest fire management system consistent with research, risk reduction, readiness, response and recovery. In fact, the relevant government agencies are still debating their respective roles and responsibilities in wildfire management; they are yet to build the human and financial capacities to adequately address wildfires.

- employ preventive measures,

- manage landscapes,

- monitor compliance and enforce laws, and;

- execute the fire management plan in the event of wildfire.

There are some headways though. Already, Forest Fire Management is supported by multiple forest co-managers, primarily non-governmental partners and community-based organizations active in the southern region (now known as the Southern Forest Fire Working Group). Muschamp has been instrumental in replicating a similar partnership with other stakeholders in the central region. “As the frequency and intensity of wildfires grow, so will the complexities, so we need to collectively plan and find cost-efficient measures to be ready to address wildfires by zones as well,” expresses Muschamp.

FUTURE OF WILDFIRES

As Climate Change will surely increase the incidences of wildfires, a more integrated Forest Fire Management is needed to minimize the threats to forest productivity and ensure that forests continue to support our national economy and local and indigenous communities (7). We note the importance of the following:

Policy Implementation: The Wildland Forest Fire Policy & Strategy 2009 needs to be revised and implemented. A national wildfire warning and response system at the community level needs to be established with stakeholders participation and inclusion.

Awareness Building: The public needs to be aware of the risks of wildfires and their vulnerabilities to their impacts.

Increase Participation: There is a need to create opportunities for community awareness, training, consultations, and other collaborative activities to support or establish regional working groups and Community Forest Fire Brigades. Such opportunities could increase government and local community interactions and foster greater collaboration between government and key stakeholders (non-government organizations, community-based groups, forest licensees and relevant government agencies) to manage wildfires in Belize.

- Global Forest Watch. Belize Fires. https://www.globalforestwatch.org/. [Online] 2022. [Cited: June 14, 2022.] https://www.globalforestwatch.org/dashboards/country/BLZ/?category=fires&location=WyJjb3VudHJ5IiwiQkxaIl0%3D&map=eyJjYW5Cb3VuZCI6ZmFsc2UsImRhdGFzZXRzIjpbeyJkYXRhc2V0IjoicG9saXRpY2FsLWJvdW5kYXJpZXMiLCJsYXllcnMiOlsiZGlzcHV0ZWQtcG9saXRpY2FsLWJvdW5kYXJpZXMiLC.

- United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction- Regional Office for the Americas and the Caribbean; United Nations Environment Programme; World Meteorological Organization; Food and Agriculture Organization. Wildfires in Latin America: A preliminary analysis, messages and resources. https://www.undrr.org. [Online] 2022. [Cited: June 16, 2022.] https://www.undrr.org/publication/wildfires-latin-america-preliminary-analysis-messages-and-resources.

- Selva Maya. Belize Forest Fire . Belmopan : s.n., 2016.

- Climate Change and Forest Disturbances: Climate change can affect forests by altering the frequency, intensity, duration, and timing of fire, drought, introduced species, insect and pathogen outbreaks, hurricanes, windstorms, ice storms, or landslides. Virginia H. Dale,Linda A. Joyce, Steve McNulty, Ronald P. Neilson, Matthew P. Ayres. 9, s.l. : Oxford Academia, 2001, Bioscience, Vol. 51, pp. 723-734.

- Oswaldo Sabido, Earl Green. Wildland Fire Strategy & Policy . Belmopan : Forest Department , 2009.

- Meerman, Jan. Provisional Report on Belize Wildfires 2011, Aftermath of Hurricane Richard. Biological Diversity Info. [Online] June 7, 2011. [Cited: September 20, 2016.] http://biological-diversity.info/Downloads/2011_Wildfire_Report.pdf.

- Percival Cho, Alan Blackburn, Jos Barlow. Investigating the effect of hurricane disturbance on fire activity in tropical forests: a GIS-based approach. [Online] 2011. [Cited: May 21, 2017.] http://www.geos.ed.ac.uk/~gisteac/proceedingsonline/GISRUK2012/Papers/presentation-81.pdf.

- Community managed forests and forest protected areas: An assessment of their conservation effectiveness across the tropics. Porter-Bolland, L.; Ellis, E.A.; Guariguata, M.R.; Ruiz-Mallén, I.; Negrete-Yankelevich, S.; Reyes-García, V. 10.1016/j.foreco.2011.05.034, 2012, Forest Ecology and Management, Vols. 268: 0378-1127, pp. 6-17.

Map Source: Fire Map, NASA, Fire Information for Research Management: https://firms.modaps.eosdis.nasa.gov/map